Build an LLM Tokenizer From Scratch

Learn to implement the Tokenizer of a GPT-like LLM in PyTorch from scratch.

We are on a journey to implement a GPT-like LLM from scratch in PyTorch.

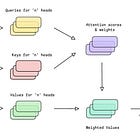

In the previous lessons, we learned how to implement Causal Multi-head Self-attention and then extended it to a full Decoder-only Transformer.

In this lesson, we will learn to build a Tokenizer that breaks down texts in the training dataset into tokens, which will later be used to train our text-generation model.

Let’s begin!

Before we start, I want to introduce you to my book, ‘LLMs In 100 Images’.

It is a collection of 100 easy-to-follow visuals that explain the most important concepts you need to master to understand LLMs today.

What is a Tokenizer?

While LLMs can generate text impressively, they do not understand language directly and only work with numbers.

A Tokenizer helps convert text into numbers or token IDs and back.

A Tokenizer internally uses a Vocabulary, which is a dictionary that maps each token to a unique token ID. The Vocabulary defines the complete set of tokens the LLM can understand and generate.

There are three main types of Tokenizers:

Character level: Split text into individual characters (“happy” → [“h”, “a”, “p”, “p”, “y”])

Word level: Split text into whole words ("hello world" → [“hello”, “world”])

Subword level: Split text into sub-words (“happiness” → [“h”, “appiness”])

Modern LLMs use subword tokenizers, some examples being:

Byte-Pair Encoding (Tiktoken) in GPT and other OpenAI models

WordPiece in BERT and DistilBERT

SentencePiece in T5, Llama, and Gemini

Subword tokenizers are popularly used and work better than the other two because they:

Help the model understand word parts like prefixes and suffixes, which helps it to learn related words that share meaning

Balance the vocabulary size well (Not too small, like for character-level tokenizers, or too large for word-level tokenizers)

Handle unknown words by breaking new words into known subwords instead of marking them using the

<UNK>token in the case of othersHelp the model handle multiple languages by breaking unknown words into subwords, removing the need for separate vocabularies for each language

Subword tokenizers like Tiktoken are complex to implement from scratch.

Since we are learning to build things with ease from the basics, we will implement a simple character-level tokenizer to train our model with.

Building a Character-level Tokenizer

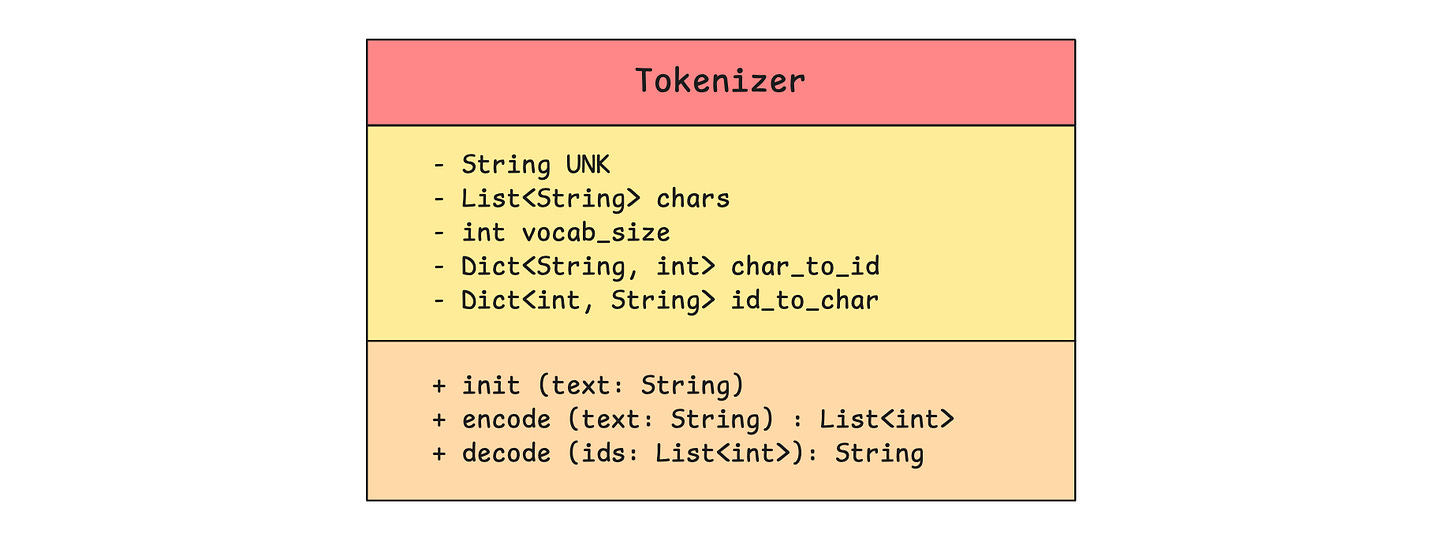

This is how our Tokenizer looks.

We represent our character-level tokenizer using the Tokenizer class.

(Although our UML class diagram uses public (+) and private (-) visibility markers, we won’t enforce strict access controls for this Python tutorial.)

class Tokenizer:

def __init__(self, text):

# Special token for characters not in vocabulary

self.UNK = "<UNK>"

# All characters in vocabulary

self.chars = sorted(list(set(text)))

self.chars += [self.UNK]

# Vocabulary size

self.vocab_size = len(self.chars)The class Tokenizer accepts text, finds unique characters, converts them into a list, and sorts the list. This is the model's Vocabulary.

The <UNK> (unknown) token is added to the vocabulary to handle characters in user prompts that weren’t in the training data, preventing crashes during encoding.

The size/ length of the vocabulary can be accessed via the vocab_size attribute.

Next, we create two dictionaries to enable conversion between characters and token IDs:

char_to_id: Maps each character to its unique token IDid_to_char: Maps each token ID back to its character

class Tokenizer:

def __init__(self, text):

# Special token for characters not in vocabulary

self.UNK = "<UNK>"

# All characters in vocabulary

self.chars = sorted(list(set(text)))

self.chars += [self.UNK]

# Vocabulary size

self.vocab_size = len(self.chars)

# Mapping from character to ID

self.char_to_id = {char: id for id, char in enumerate(self.chars)}

# Mapping from ID to character

self.id_to_char = {id: char for id, char in enumerate(self.chars)} Following this, we add two methods to the Tokenizer class as follows:

encode: Converts a text string into a list of token IDs. If a character isn't in the vocabulary, it gets mapped to the<UNK>token ID.decode: Converts a list of token IDs back into a text string. If a token ID isn't found, it returns the<UNK>token.

# Character level tokenizer (Characters are tokens)

class Tokenizer:

def __init__(self, text):

# Special token for characters not in vocabulary

self.UNK = "<UNK>"

# All characters in vocabulary

self.chars = sorted(list(set(text)))

self.chars += [self.UNK]

# Vocabulary size

self.vocab_size = len(self.chars)

# Mapping from character to ID

self.char_to_id = {char: id for id, char in enumerate(self.chars)}

# Mapping from ID to character

self.id_to_char = {id: char for id, char in enumerate(self.chars)}

# Convert text string to list of token IDs

def encode(self, text):

return [self.char_to_id.get(ch, self.char_to_id[self.UNK]) for ch in text]

# Convert list of token IDs to text string

def decode(self, ids):

return "".join(self.id_to_char.get(id, self.UNK) for id in ids)And that completes the implementation of our simple character-level Tokenizer.

Let’s learn to use it next.

Working with our Tokenizer

We will use the sentence "the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog" as our sample training data when we instantiate the tokenizer.

# Training text

training_text = "the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog"

# Instantiate the tokenizer

tokenizer = Tokenizer(training_text)This creates the vocabulary as follows.

# Vocabulary

print(f"Vocabulary: {tokenizer.chars}")

"""

Output:

Vocabulary: [' ', 'a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f', 'g', 'h', 'i', 'j', 'k', 'l', 'm', 'n', 'o', 'p', 'q', 'r', 's', 't', 'u', 'v', 'w', 'x', 'y', 'z', '<UNK>']

"""# Vocabulary size

print(f"\nVocabulary size: {tokenizer.vocab_size}")

"""

Output:

Vocabulary size: 28

"""Let’s look at the character-to-token-ID mapping to better understand the tokenizer's internals.

print(f"Character to ID mapping:")

for char, id in tokenizer.char_to_id.items():

print(f"'{char}' → {id}")

"""

Output:

Character to ID mapping:

' ' → 0

'a' → 1

'b' → 2

'c' → 3

'd' → 4

'e' → 5

'f' → 6

'g' → 7

'h' → 8

'i' → 9

'j' → 10

'k' → 11

'l' → 12

'm' → 13

'n' → 14

'o' → 15

'p' → 16

'q' → 17

'r' → 18

's' → 19

't' → 20

'u' → 21

'v' → 22

'w' → 23

'x' → 24

'y' → 25

'z' → 26

'<UNK>' → 27

"""We see that the vocabulary includes token IDs for blank and the <UNK> (unknown) character.

The token ID-to-character mapping looks similar, but with the items swapped around the arrows, and it is not shown.

Let’s encode the sentence “hey, what’s up?” using our tokenizer.

token_ids = tokenizer.encode("hey, what’s up?")

print(token_ids)

# Output: [8, 5, 25, 27, 0, 23, 8, 1, 20, 27, 19, 0, 21, 16, 27]Next, we will convert these token IDs back to a text string.

text_string = tokenizer.decode(token_ids)

print(text_string)

# Output: hey<UNK> what<UNK>s up<UNK>We see that tokens not part of the vocabulary (comma, apostrophe, question mark) are replaced by the <UNK> token in the decoded text.

If we did not have the <UNK> token, the encoding followed by decoding would have thrown an error.

That’s everything for this lesson on Tokenizers.

In the next lesson, we will use it to tokenize a training dataset and train our text-generation model.

If you are struggling to understand this article well, start here:

This article is free to read, so share it with others. ❤️

If you want to get even more value from this publication and support me in creating these in-depth tutorials, consider becoming a paid subscriber for just $50 per year.

You can also check out my books on Gumroad and connect with me on LinkedIn to stay in touch.